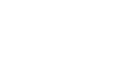

The Great Lakes is a chain of inland lakes – Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, and Lake Superior – stretching from New York to Minnesota.

Because they comprise such a large waterway, they have played a vital role in the lives and histories of Indian peoples who have resided along their shores for millennia. Most Indian groups living in the Great Lakes region for the last five centuries are of the Algonkian language family. This includes such present-day Wisconsin tribes as the Menominee, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi. Some tribes, such as the Stockbridge-Munsee and the Brothertown, are also Algonkian-speaking tribes who relocated from the eastern seaboard to the Great Lakes region in the 19th century. The Oneida who live near Green Bay belong to the Iroquois language group and the Ho-Chunk of Wisconsin are one of the few Great Lakes tribes to speak a Siouan language.

Although there have been many differences in language and customs between different Indian tribes, Great Lakes Indian communities have had many things in common. They comprise a general culture called "Woodland" after its adaptation to North America's northeastern and southeastern woodlands. Woodland Indian societies have depended to a large degree on forest products for their survival, and Great Lakes Indians hunted, fished, gathered wild foods, and practiced agriculture for their subsistence. In many parts of the Great Lakes -- particularly northern Wisconsin -- Indians depended on wild rice as a dietary staple, while Indians in areas without wild rice generally cultivated corn. Where sugar maples grow, Great Lakes Indians established sugar-making camps in early spring and made sugar from tree sap.

Establishing Trade

Establishing Trade

The exact date of initial European contact with the Great Lakes Indians is unknown. During the early 1500s, European ships and fishing crews off the coast of northeastern Canada often traded with Indians there. The first recorded contact between Europeans and the Great Lakes Indians occurred between 1534 and 1542, when Jacques Cartier of France explored the St. Lawrence River. His failure to find gold or silver reduced French interest in North America but, despite this, Samuel de Champlain established the city of Quebec and along with it the colony of New France in 1608. The French quickly developed a military and economic alliance with neighboring Algonkian tribes and the Iroquoian-speaking Huron near Lake Huron. Soon, the Dutch of New Netherland established a rival colony in present-day New York, and developed similar trade networks with the five Iroquois nations (the League of the Iroquois) in upstate New York. Later, when the English conquered New Netherland in 1664 and renamed it New York, the Iroquois transferred their loyalties to the English. In the 1640s, the Iroquois began a series of wars in the Great Lakes region mainly motivated by the rich fur-bearing lands of other Indian groups, completely wiping out some tribes, including the Erie, and scattering others such as the Huron from their original homelands. The wars between the Iroquois League and the French-allied tribes persisted until 1701, although there were long periods of relative peace during that time.

These wars radically changed the human landscape of the Great Lakes region. Tribes in Michigan's southern peninsula -- the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Sauk, Fox, and Ottawa -- were pushed farther west into Wisconsin during the 1600s. Some tribes that moved into Wisconsin because of the Iroquois wars, including the Huron, Miami, Sauk, Fox, Mascouten, and Kickapoo, left Wisconsin during the 1700s for new lands west of the Mississippi or other parts of the Midwest. Some refugees of the Iroquois wars, namely the Potawatomi and Ojibwe, stayed in Wisconsin.

Introduction of Disease

Indian people of the Great Lakes also suffered from European diseases, which often devastated their communities. Unlike Europeans, Indians did not have natural immunities to diseases such as smallpox, measles, or mumps because these diseases did not exist in North America before whites came. After Europeans arrived, these diseases often wiped out whole Indian villages. The Ho-Chunk, for example, were said to have had between 4,000 and 5,000 people when Nicolet first arrived among them in 1634. When French traders came back 20 years later, the Ho-Chunk had been reduced to only 600 or 700 members. While wars with the Iroquois and other refugee Indian groups played a part in this rapid decline, European diseases were probably the main cause for the dramatic number of deaths.

Some the first Europeans to come to the Great Lakes region were Christian missionaries. One of the most active groups was the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits, a Roman Catholic religious order that first started to preach among the Iroquoian-speaking Hurons of Lake Huron in 1625. By 1665, they had established missions at Chequamegon Bay in Lake Superior and at Green Bay in 1669. While the Jesuits enjoyed some successes, they required rigid standards for potential converts and thus did not convert large numbers of Indians to Christianity. Whatever progress they made was lost after 1728 when they abandoned their mission stations in Wisconsin because of the Fox Wars, during which the Fox Indians rose up against French authority. The Fox Wars ended in the 1730s, but the French were unable to send new missionaries to Wisconsin afterward. The next Christian missionaries did not arrive until the 1820s, and they represented both the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations.

Some the first Europeans to come to the Great Lakes region were Christian missionaries. One of the most active groups was the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits, a Roman Catholic religious order that first started to preach among the Iroquoian-speaking Hurons of Lake Huron in 1625. By 1665, they had established missions at Chequamegon Bay in Lake Superior and at Green Bay in 1669. While the Jesuits enjoyed some successes, they required rigid standards for potential converts and thus did not convert large numbers of Indians to Christianity. Whatever progress they made was lost after 1728 when they abandoned their mission stations in Wisconsin because of the Fox Wars, during which the Fox Indians rose up against French authority. The Fox Wars ended in the 1730s, but the French were unable to send new missionaries to Wisconsin afterward. The next Christian missionaries did not arrive until the 1820s, and they represented both the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations.

Intermarriage and Economic Change

Another important aspect of contact between Europeans and Great Lakes Indians was intermarriage. Many young English, Scottish, and especially French men went west in the 1600s and 1700s to gather furs from the Indians, but because very few European women accompanied them, many traders took Indian women as their wives. Unlike Europeans, Indians did not use race as the basis for exclusion or inclusion into their societies, and the children of these unions were welcomed into the tribal societies. These intermarriages are one reason that so many Indians in Wisconsin and the Great Lakes have European, and especially French last names today. Not all children of Indian-white marriages joined their mothers' tribes. Some Indian women raised their children in fur-trading towns such as Green Bay, Prairie du Chien, and Mackinac Island. While these children were of Indian heritage and usually knew the languages and customs of their mothers' tribes, they did not consider themselves to be Indians. They thought of themselves as métis, which was a French word meaning "mixed blood." There were métis communities throughout the Great Lakes region during the 1700s and early 1800s.

All tribes in Wisconsin during the 1600s and 1700s were anxious to trade furs for European goods. The French, Dutch, and English were especially interested in beaver pelts, which were sent to Europe to make hats. In turn, the Indians received European manufactured goods such as guns, cloth, knives, and metal cooking utensils. Besides the impact of these material goods, there were other major changes as well. Rather than living in large villages, Indian people began to spread out over wider areas and live in smaller, more mobile settlements. In spring and summer, these villages were generally located along waterways where the soils were good for raising corn, squash, and beans and where people could also concentrate on fishing. In winter, the Indians abandoned these villages and dispersed to create small, family-sized hunting camps and focus on hunting and acquiring furs for trade. Although linked to other villages of the same tribe, villages were generally autonomous and independent of other Indian villages. As time went on, Indian people became more dependent on European trade goods and were drawn into European economic systems. At the same time, they were also drawn into the political and military schemes of their European trade partners and allies.

Pontiac's Rebellion

Between 1689 and 1763, the French and British fought a series of four wars for control of North America. The final conflict, the French and Indian War (also called the Seven Years' War), lasted from 1754 to 1763. During this war, the League of the Iroquois sided with the British, while the Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi allied with the French. When the war ended, the British had won control of all former French possessions in Canada and the Midwest. The British treated the former Indian allies of the French like conquered peoples, which prompted the Ottawa chief Pontiac from the Detroit area to lead a rebellion of a number of tribes against the British. During Pontiac's Rebellion, Indian forces captured and laid siege to many British forts, including those at the Straits of Mackinac and Detroit. By 1765, the British managed to regain control of the region and end Pontiac's Rebellion.

Pontiac's Rebellion taught the British that colonial power in the Great Lakes depended on developing better relations with the Indians. This strategy paid off, for when the American Revolution began, almost all Great Lakes Indians sided with the British against the Americans. However, the Potawatomi at Milwaukee and around the southern shore of Lake Michigan sided with the Americans during the Revolution. America gained sovereignty over the southern Great Lakes region when the British surrendered its control over lands west of the Appalachian mountains in the 1783 peace treaty. Despite this, many Indians in the Great Lakes region continued their strong attachments to the British because they feared the United States would take away their lands. The Indians of the Ohio River valley fought against American expansion in the early 1790s and defeated two American armies sent to conquer them. Finally, the United States defeated the Ohio Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

Great Britain and Tecumseh

The final battle between Britain and the United States for control over the Great Lakes came during the War of 1812. Many British officials believed that the United States wanted to take Canada from Great Britain. The British continued to cultivate good relations with the Indians and even promised to establish an independent Indian state in the Great Lakes region to act as a buffer between the United States and Canada. Prior to the War of 1812, two Shawnee Indians from Ohio -- Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (also called the Shawnee Prophet) -- created a formidable pan-Indian alliance to prevent further American expansion west of the Appalachians and allied with the British against America. Although the British and their Indian allies enjoyed great success in Wisconsin and the upper Great Lakes region, the British once again lost this area to the Americans when peace was made in 1814.

Black Hawk or Makataimeshekiakiah (1767-1838)

Black Hawk or Makataimeshekiakiah (1767-1838)

Black Hawk was a Sauk man known for his exploits in war. He led a group of Sauk known as the "British band," who maintained trade contacts with the British after the War of 1812. In the decades followed, he opposed removing to new lands west of the Mississippi. In 1832, Black Hawk and his band returned to Illinois at the invitation of the Potawatomi, but the governor of Illinois called up a militia to force them out and began what is called the "Black Hawk War." The American army chased the Sauk, Fox, and other Indian forces into Wisconsin, where many were killed at the Battle of Bad Axe. Black Hawk was captured, ending the war. In 1833, the captured Indian leaders were taken to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Jackson, and Black Hawk was widely admired by the American people, despite having fought against them. The Indian leaders, including Black Hawk, were released by the federal government in 1837, and returned to the Sac and Fox tribe, where they were accepted back by the Sac and Fox leader Keokuk.

(Image painted at Detroit, 1833. From James Otto Lews, Indian Portfolio, 1835, Philadelphia)

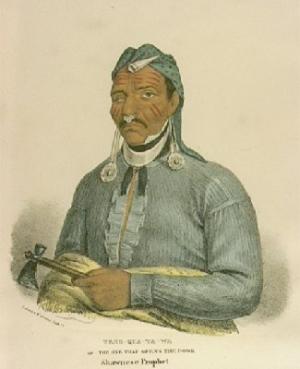

Tens-qua-ta-wa

Tens-qua-ta-wa

Tens-qua-ta-wa, also known as the Shawnee Prophet, was the brother of the famed Shawnee Indian leader Tecumseh, who sided with the British during the War of 1812. Tens-qua-ta-wa began giving predictions and preaching a message of resistance to White encroachment in 1806. He and his followers established a village on the Wabash River called Prophet's Town. Both he and Tecumseh stated that earlier treaties were invalid because no single tribe had a right to surrender land to Whites without the agreement of all the tribes.

(Image painted at Detroit, 1833. From James Otto Lews, Indian Portfolio, 1835, Philadelphia)

Removal

Following Indian land sales, the United States pursued a policy called Indian removal whereby Great Lakes tribes were to be removed west across the Mississippi. Other Great Lakes tribes in southern Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were forced to leave their homes in the Midwest for new lands in Kansas and Oklahoma. In Wisconsin, however, the United States failed to completely remove any of the tribes. Most of the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Ottawa who lived in southern Wisconsin were removed to Kansas in the 1830s, but some Potawatomi refused to go and instead moved to northern Wisconsin. About half of the Ho-Chunk removed to Iowa, and were later moved to Minnesota, South Dakota, and finally Nebraska. The other half of the tribe refused to move out of Wisconsin. The federal government attempted to remove the remaining Wisconsin Ho-Chunk to Nebraska in 1873 and 1874, but most returned to Wisconsin within a year. The Menominee and the Ojibwe also refused to leave, and in 1854 they received reservation lands so they could stay in Wisconsin.

Assimilation

From about 1850 to 1930, the United States developed an assimilation policy through which Indian people were encouraged or forced to give up their languages, customs, religions, and ways of life. They were forced to live like whites so they could be "civilized" and eventually assimilate or fit into mainstream American society. Many whites did not understand that Indian people already had their own civilizations and cultures that they did not want to give up. The two primary institutions the United States used to implement its assimilation policy were boarding schools and land allotments. Boarding schools were run by the government or by religious groups and focused on teaching Indian boys agriculture and manual trades, while Indian girls were taught domestic skills. The largest and most well-known boarding school was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania established in 1879. The superintendent of Carlisle and other boarding schools believed it was necessary to separate children from their tribes and families so they could be purged of their "savage" lifestyles. The other tool that white reformers used to assimilate Indians were land allotments, which were mandated by the 1887 Dawes Act. Rather than letting tribes hold their reservation lands communally, lands were divided up and allotted to individuals so they could farm. However, most Indians did not want to farm and often sold their lands, often to non-Indians. By 1920, over 90% of the land on some reservations, such as the Oneida reservation in northeastern Wisconsin, was owned by whites.

U.S. assimilationist policies ended in the 1930s largely because Indians did not want to give up their culture and wanted to remain Indians. The federal government attempted a similar program in the 1950s called Termination in which tribes would no longer be recognized as sovereign political bodies by the federal government. The Menominee were terminated as a tribe in 1961, but their experience with this new program was so negative that no other tribe agreed to be terminated. The Menominee fought to regain their status as a federally recognized tribe, accomplishing this in 1973. Moreover, the Wisconsin Ho-Chunk managed to gain federal recognition in 1963 over a century after they had sold their lands in Wisconsin. In the last 25 years, Great Lakes Indian tribes have endeavored to restore their political sovereignty. In 1983, the Ojibwe won an important court case: Wisconsin Ojibwe bands asserted that Wisconsin wrongly curtailed their rights to spearfish on lands they had ceded in earlier treaties. The Ojibwe rightly argued that they never gave up the right to hunt and fish off their reservations, as their treaties clearly state. The Great Lakes tribes have also become more prosperous through casino gambling, which is allowed on reservation lands because of the political sovereignty tribes have retained.