By Valerie J. Davis

Schoolgirl samplers are familiar and endearing embroidered textiles closely associated in the public consciousness with genteel female education, needlework artistry, and early American history. The earliest recognizable samplers were created in Europe in the sixteenth century by professional and amateur needleworkers as repositories for favorite stitches and patterns for later applications. Despite this early purpose, the vast majority of embroidery samplers that exist today were not made by mature women, but by young girls as part of their formal education.

Two hundred years later, in the eighteenth century, embroidered samplers as mere memory aids disappeared and samplers became an integral part of the school curriculum in genteel female education. They were educational tools, much like a slate or horn board, that strived to develop a young girl’s stitchery skills for both practical and ornamental purposes. Samplers also developed secondary functions as girls were made to sew upon them verses, poems, or tracts concerning life and death, and the rewards of pious behavior. The execution of verses on samplers, with increasingly more elaborate decorative motifs and designs, provided practice for more intricate stitches and designs along with the hope that reproducing such sentiments on cloth would foster virtue, publicly exhibiting moral and needlework accomplishments.

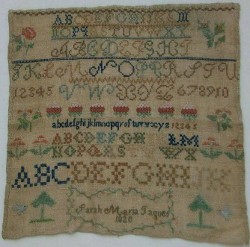

Most girls’ sewing education began with simple marking samplers consisting of several cross stitched alphabets, numerals, and perhaps a few simple geometric motifs placed in ordered, horizontal rows. After their completion, the makers of these marking samplers could often go on to produce more intricate and individually designed pieces. For other girls, the marking sampler was the extent of their needlework education. Samplers that depict maps, genealogical information, or detailed architectural elements were also produced by young girls who benefited from a broadened educational curriculum that later covered subjects like geography, civics, and the natural sciences.

As there was no standardization of curriculum, a girl could learn only what her teacher was skilled enough to teach, but the multitude of available teaching situations throughout the eighteenth century were diverse enough and in demand by concerned parents and community leaders, that most girls received some sort of education no matter their social and economic circumstances. Whether made in elite academies, boarding schools, formal or informal day schools, orphanages, charity schools, or in an apprenticed or indentured work situation, the overwhelming majority of learning situations for girls, up until the mid-nineteenth century, utilized the sampler as a teaching tool. While some sampler’s styles can be traced to a specific school, teacher, region, country, or particular learning environment, many samplers are anonymous. What we can know of each one that has survived is that these beloved textiles today were valued when they were made and were often framed and displayed on walls, many kept within families as cherished heirlooms.

Every sampler is a historical record of one girl’s educational training and the type and value placed on that education. The overall design, materials used, and design motifs give evidence of her culture, religion, social class, and personal artistic accomplishments and abilities. For well-educated girls of high social class, samplers confirmed their genteel standing; for the middling sort, samplers established their family’s place in an emerging American middle class. Samplers also benefited the poor or orphaned girl by teaching her a trade in practical, marketable sewing skills for future self employment. Sampler making was also seen as laying the groundwork for religious piety, family responsibility, and civic virtue. Through its completion the young girl established, in a most public way, her educational accomplishments and the importance her family and community placed on that education.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, needlework, once a measure of gentility, became relegated to an elective subject in female academies. The gradual spread of public education and co-education among all classes of people pushed sampler-making from the classroom to a pastime at home. The increased use and availability of ink to mark textiles replaced the laborious cross stitched letters on clothing and household textiles, and the increased availability of paper, pencils, slates, and blackboards were the preferred method for practicing letters and numbers.

Educational reforms in the late-nineteenth century may have diminished the importance of needlework skills, but it did fuel the Arts and Crafts movement in the twentieth century and subsequent Colonial Revival movements. The appreciation of and scholarship in needlework samplers for their beauty, evidence of early women’s history, and educational methodology and reform, has led to increased interest in this form of female expression into the twenty-first century.