Figure 19: Salt-glazed stoneware from the collection.The DuBay collection consists of pottery, glass bottles, metal tools, charred wood, and even a few textiles recovered from the site of John DuBay’s homestead. Bones from domestic animals were also recovered which helped archaeologists to date the materials. There are over one hundred complete or restored artifacts in the collection and thousands of fragments. The objects below are the best preserved and serve as a representation of the entire collection.

Ceramics

Earthenware

Earthenware ceramics were made from common glacial and alluvial soils throughout the world. The resulting pottery was permeable by water and food residues so it was usually glazed. The pottery in the DuBay collection was mostly manufactured in Great Britain and New England.

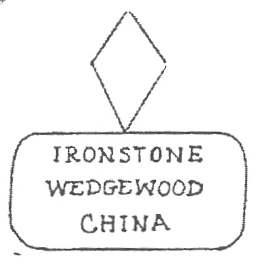

Figure 20: Complete earthenware mold-decorated bowl, Wedgewood, Turnstall, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1860-1885 (Figure 22 in Wackman 1991).

Figure 21: Detail of maker's mark (Wackman 199:54: Figure 22).

Figure 22: Clay pipe bowl white clay, no maker’s mark. (Wackman 1991: Figure 36b).

Salt-glazed Stoneware

The high degree of vitrification in the firing process and the fine-grained clay used in manufacture made salt-glazed stoneware hard, durable, and non-porous, giving it a high value in food processing and storage. Salt-glazed stoneware was produced in Germany and England dating back to the sixteenth century. In 1775, the first New England manufacturer of the pottery was established. The clay used in the manufacture of salt-glazed stoneware had to be imported from Ohio, Illinois, and other states. There were small potteries in Wisconsin producing the stoneware, but most came from factories in Ohio. It was determined that the items in the DuBay collection were manufactured after 1840, due to the presence of Albany Brown, a brown glaze, in the interior of the stoneware.

Figure 23: Four gallon storage crock (Wackman 1991: Figure 9).

Figure 24: Gallon small-mouthed jug (Wackman 1991: Figure 15).

Figure 25: Half gallon tomato or fruit jar (Wackman 1991: Figure 14).

Porcelain

Porcelain was the “highest form” of ceramics. It is manufactured from fine, white grain clay. The term “china” originated from the birthplace of porcelain, China. Imports from England in the nineteenth century were thick, plain, and hardy, unlike the beautiful, decorative tableware from Asia. Settlers like the DuBays would have no use for delicate, decorative tea sets, instead preferring functional pieces mass-produced in England.

Figure 26: “Frozen Charlotte Doll,” black, unglazed, ca. 1850-1885 (Wackman 1991: Figure 26).

Figure 27: Set of four matched cups, no maker’s mark, porcelain.

Figure 29: Cup and saucer.

Figure 29: Cup and saucer.

Figure 28: Set of five miniature porcelain saucers, four cups, and one lid. Davenport, ca. 1850-1855 (Wackman 1991: Figure 27).

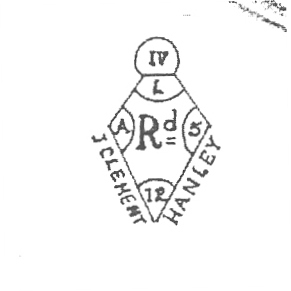

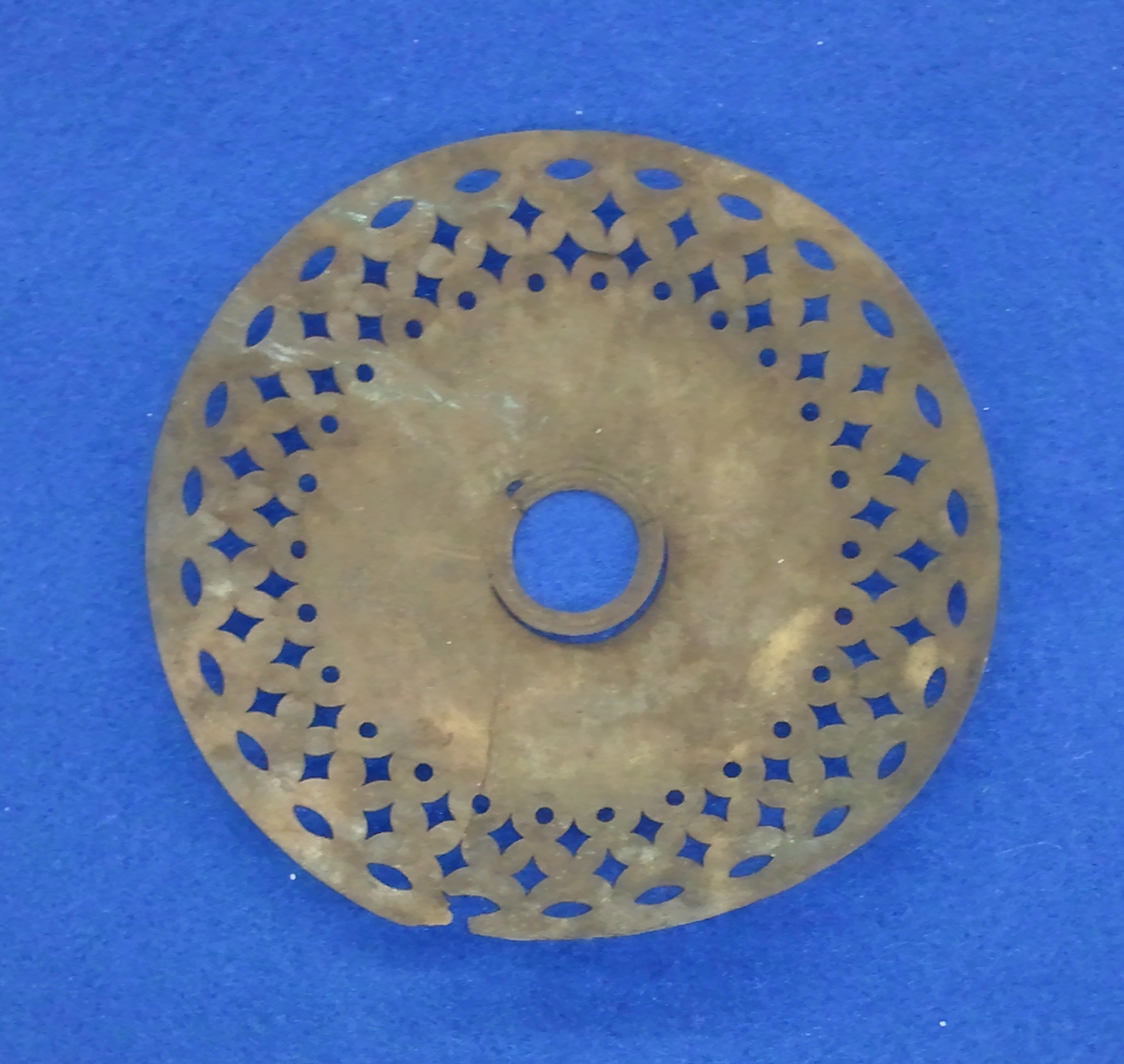

Figure 30: Complete saucer, J. Clementson, Hanley, Staffordshire, England, “New York Shape,” ca. 1856 (Wackman 1991: Figure 23). Currently on display in the Wisconsin Archaeology exhibit on the second floor of the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Figure 31 Detail of maker's mark (Wackman 1991:55: Figure 23).

Figure 32: Painted porcelain jar or teapot lid, no maker’s mark.

Glass

Figure 33: Medicine bottles found at the DuBay Site.

Many common household products and foods were bought in glass bottles. Fragments from nearly 45 different bottles were found at the DuBay site. Some of the most common forms were bottles holding liniments, medicines, or alcohol. Four nearly-complete glass flasks were recovered from the site as well as soda water, or mineral water bottles. Because of the collecting value of glass bottles, they were relatively easy to date as being from the mid to late nineteenth century. Archaeological Rescue was also able to date the DuBay homestead from the sheet glass used in windows. Based on the thickness of known models, they determined that most of the broken pane glass found at the DuBay site was 0.085 inches thick, used approximately from 1855-1885. Fused glass was also found onsite, leading them to believe the site had been destroyed in a fire.

Figure 34: Two complete liniment bottles, “Johnson’s American Anodyne Liniment,” possibly from Johnson, Nelson & Co., Detroit, Michigan, or Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, ca. 1890 (Wackman 1991:Figure 28).

Figure 34: Two complete liniment bottles, “Johnson’s American Anodyne Liniment,” possibly from Johnson, Nelson & Co., Detroit, Michigan, or Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, ca. 1890 (Wackman 1991:Figure 28).

Figure 35 (Front) Historical flask, “For Pikes Peak,” associated with the gold rush ca. 1859-1860 (Wackman 1991: Figure 29).

Figure 36 (Back) Historical flask, “For Pikes Peak,” associated with the gold rush ca. 1859-1860 (Wackman 1991: Figure 29).

Figure 37: Round-bottom mineral water bottle, “SEE THAT EACH CORK IS BRANDED … & COCHRANE … LIN & BELFAST”, ca. 1860-1880 (Wackman 1991: Figure 31).

Metal

Gun Components

Figure 38: Various cartridges (Wackman 1991: Figure 42). (Clockwise from Upper Left): (1) .45-.75 Winchester, Model 1876 Centennial lever-action repeater; (2) .32 long, Smith and Wesson New Model #2 revolver; (3) .44 Henry; (4) .45-.75 Winchester; (5) .44 Henry, 1860-1866, Colt revolver. The variety of cartridges suggests that DuBay kept a number of different models of guns at his home.

Figure 39: Back-action gun lock (Wackman 1991: Figure 43).

Tools

Figure 40: Tools (Clockwise from bottom left): wrench, scythe snath (held scythe blade in place on wooden handle), file, tinker’s hammer used to manipulate and shape tin (Wackman 1991: Figure 44) and anvil punch.

Figure 41: Portion of crosscut saw.

Household Items

Figure 42: Knife, fork, and partial spoon.

Figure 43: Silver trade brooch (Wackman 1991: Figure 47). Usually worn by Indian women and used in trade.

Figure 44: Unidentified textile.

Figure 45: Leather shoe soles.

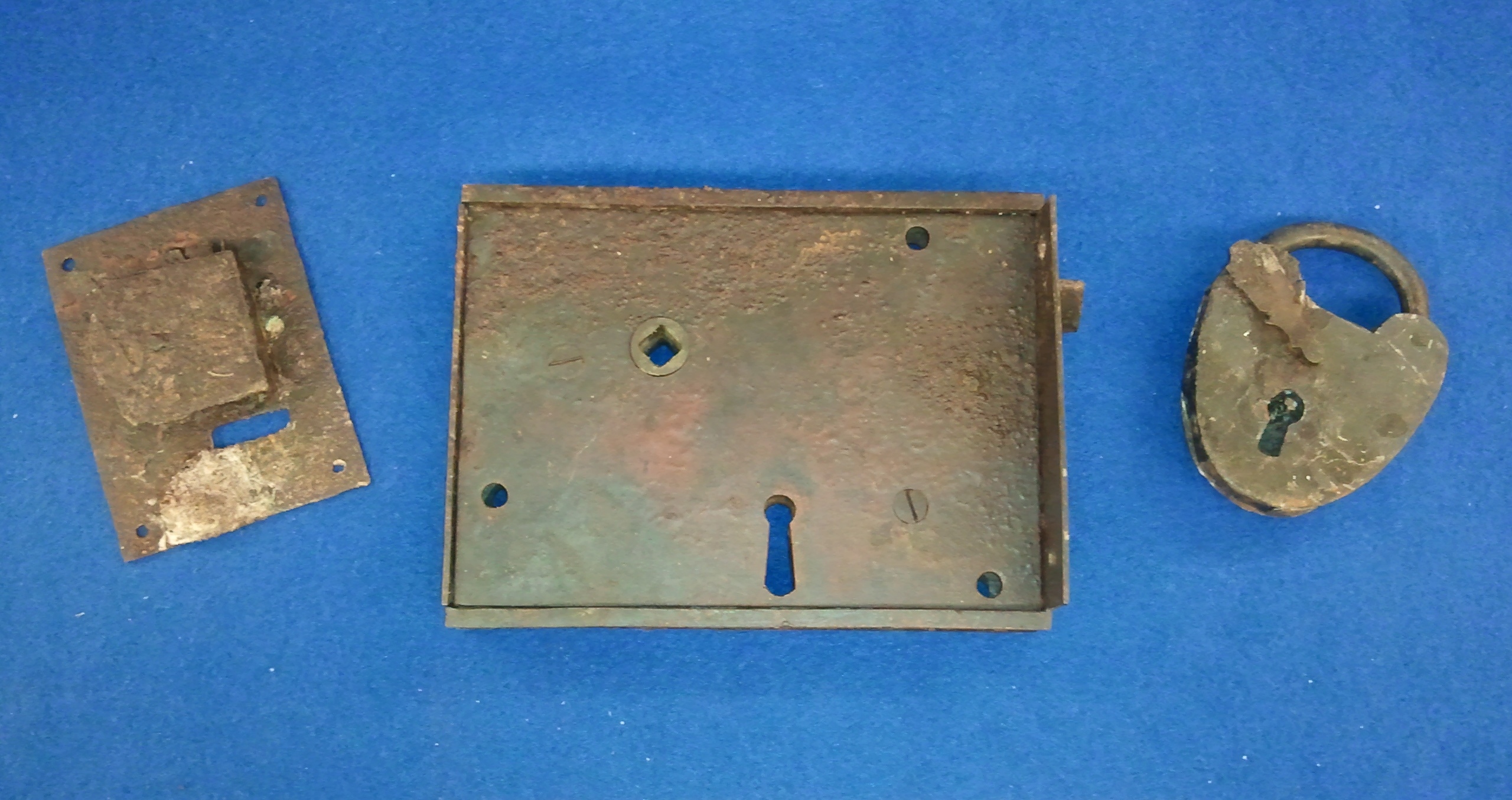

Figure 46: Miscellaneous locks (from left) small lock, large gate or door lock, bronze padlock.